Analyzing accuracy of power reported by stationary bike [see within blog graph]

I was curious how effort exerted during the exercise impacts heart rate and whether that correlates strongly with subjective fatigue and exhaustion.

It seemed that easiest way to experiment would be stationary bike. Running only has single variable, speed. One could of course change incline, but that would be harder to predict.

For elliptical machine or rowing machine it would be even more complicated!

With stationary bike, there are two variables that potentially impact power you need to exert:

- RPM (revolutions per minute), or angular velocity, that should have linear effect on power (no air resistance as it's stationary!)

- resistance, which isn't exactly specified, but one would expect it to be proportional to the force you have to apply (i.e. torque)

Or, simply put, $P = \tau \omega$ (wiki )

The indoor exercise bike displays the pace (i.e. revolutions per minute), so all you have to do is maintain it. In addition it's displaying current resistance level (you can set it by adjusting a mechanical knob) and reports power in watts.

During exercise, I'm using a chest HR tracker, so simplest thing to do would be take whatever power the machine reports and try to find correlation with moving total/average of HR.

However, being paranoid and lacking any documentation for the machine, I decided no to trust its numbers blindly and check them instead. Technogym's website doesn't help in clarifying how power is computed. They have some sensible information like:

The power meter must be accurate.

The power measurement must be precise and repeatable. A 3-5 watt error is not significant, but if a system is not reliable there may be deviations of many tens of watts, i.e. equal to or greater than the amount of power that is gained from one year's training.

Let's see how accurate is their power meter!

Initial measurements (2019-11-09)¶

Throughout different exercise sessions, I've taken bunch of measurements of RPM, resistance and power:

Measurements

# TODO could only collapse inputs?

datas = """

58 10 129

56 10 127

56 10 127

56 8 94

57 8 98

56 8 94

58 10 133

56 10 126

56 8 93

55 8 91

56 8 94

56 10 128

55 10 124

54 10 119

53 8 87

55 8 93

55 8 90

95 8 240

70 10 198

55 8 85

95 8 226

95 8 229

95 8 228

95 8 227

97 8 236

95 8 227

95 8 227

95 8 230

60 10 156

61 10 154

62 10 162

61 10 156

55 10 125

56 10 128

57 8 89

56 8 87

57 8 90

57 8 91

60 8 101

56 10 129

57 10 131

"""

import pandas as pd

def make_df(datas: str) -> pd.DataFrame:

df = pd.DataFrame(

(map(int, l.split()) for l in datas.splitlines() if len(l.strip()) > 0),

columns=['rpm', 'resistance', 'watts'],

)

df.index = df.apply(lambda row: f"{row['rpm']}_{row['resistance']}_{row['watts']}", axis='columns')

return df

df = make_df(datas)

old_df = df.copy()

# btw, if anyone knows a more elegant way of converting such a table in dataframe, I'd be happy to know!

display(df.sample(10, random_state=0))

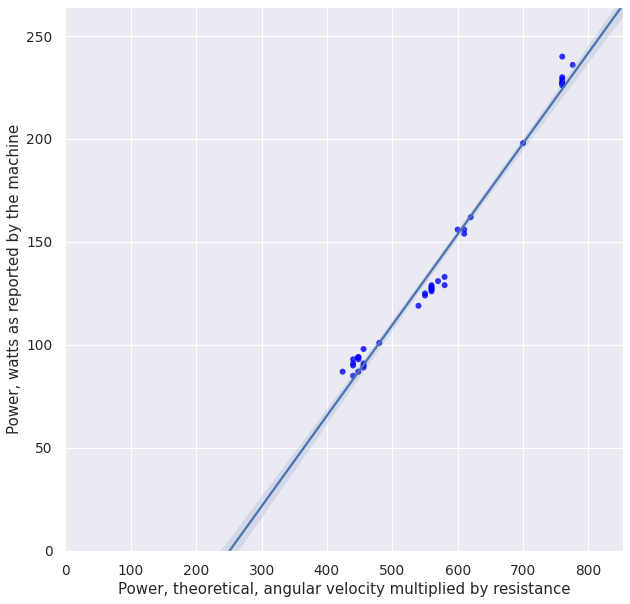

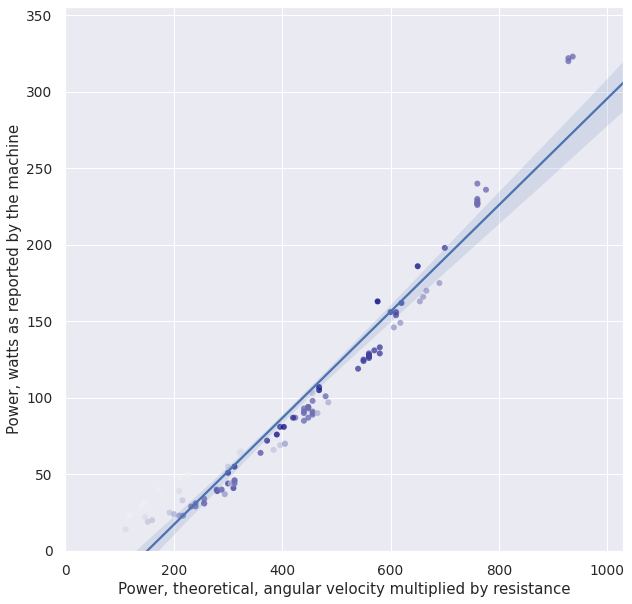

It's reasonable to assume that power depends linearly both on RPM and resistance, so we conjecture watts = rpm x resistance. Let's see if it holds against what the exercise bike reports:

hack to make seaborn plots deterministic

import seaborn as sns

if sns.algorithms.bootstrap.__module__ == 'seaborn.algorithms':

# prevents nondeterminism in plots https://github.com/mwaskom/seaborn/issues/1924

# we only want to do it once

def bootstrap_hacked(*args, bootstrap_orig = sns.algorithms.bootstrap, **kwargs):

kwargs['seed'] = 0

return bootstrap_orig(*args, **kwargs)

sns.algorithms.bootstrap = bootstrap_hacked

# apparently because of a dependency

# https://github.com/statsmodels/statsmodels/blob/fdd61859568c4863de9b084cb9f84512be55ab33/setup.cfg#L17

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore', 'Method .ptp is deprecated and will be removed.*', FutureWarning, module='numpy.*')

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('seaborn')

import seaborn as sns

sns.set(font_scale=1.25) # TODO not sure?

def plot_df(df):

dff = df.copy()

dff['rpm x resistance'] = df['rpm'] * df['resistance']

if 'color' not in dff:

dff['color'] = 'blue'

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 10))

plt.xlim((0, max(dff['rpm x resistance']) * 1.1))

plt.ylim((0, max(dff['watts']) * 1.1))

g = sns.regplot(

data=dff,

x='rpm x resistance', y='watts',

ax=ax,

scatter_kws={'facecolors':dff['color']},

truncate=False,

)

plt.xlabel('Power, theoretical, angular velocity multiplied by resistance')

plt.ylabel('Power, watts as reported by the machine')

plt.show()

plot_df(df)

Wow, that doesn't look so well, I'd expect the regression line to intersect (0, 0). Let's double check this:

import statsmodels.api as sm

def print_stats(df):

dff = df.copy()

dff['rpm x resistance'] = df['rpm'] * df['resistance']

X = dff[['rpm x resistance']]

X = sm.add_constant(X)

res = sm.OLS(dff['watts'], X).fit()

summary = str(res.summary())

import re # filter out nondeterministic stuff from the report

summary = re.sub('Date:.*\d{4}.*\n', '', str(summary))

summary = re.sub('Time:.*\d{2}:\d{2}:\d{2}.*\n', '', str(summary))

print(summary)

print_stats(df)

Free parameter is about -100 watts, which is quite a lot considering my high intensity intervals are 250 watts (so it means about 40% error!).

I don't think it can be explained by friction either: if anything, friction would shift the plot up and make the free coefficient positive.

At this point, I'm not sure what it means. I guess I'll try to make more measurements at really low resistances and speeds to make the model more complete, but I would be too surprised if either watts or resistance reported by the machine are just made up.

More data (2019-11-14)¶

I collected more data corresponding to different resistances/velocities. It's actually quite hard to consistently spin under low resistance setting, so I think I might need one more round of data collection to complete the picture!

More measurements

new_df = make_df("""

96 4 66

99 4 69

101 6 146

103 6 149

110 6 166

111 6 170

50 13 186

36 13 107

36 13 105

31 10 41

30 10 44

28 10 39

117 8 323

116 8 320

116 8 322

48 6 40

49 6 37

60 2 24

59 2 23

86 2 40

106 2 48

62 5 44

61 5 44

81 5 70

81 5 70

93 5 90

97 5 97

35 12 87

33 12 81

25 12 51

26 12 55

27 1 50

39 8 46

39 8 44

30 8 29

30 8 31

32 8 31

32 8 31

29 8 29

""")

df = pd.concat([old_df, new_df])

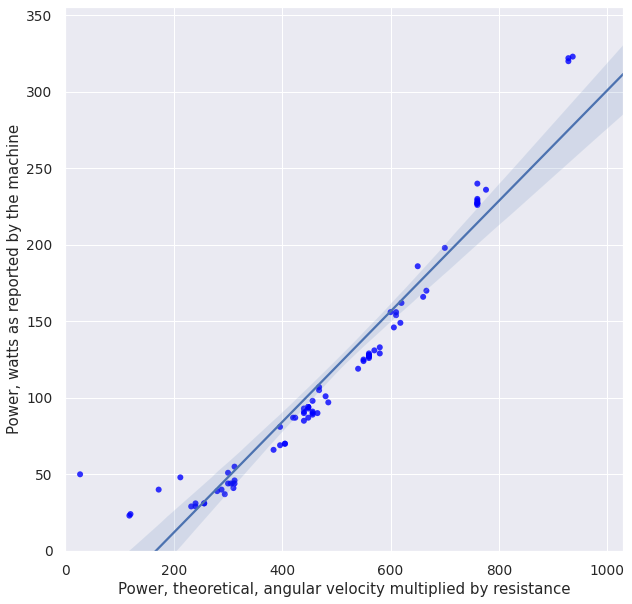

plot_df(df)

print_stats(df)

Ok, it clearly started diverging from the nice linear dependency, especially at lower values of theoretical power. It's time to try to break it down and see what is to blame: e.g., resistance or speed component, or perhaps some individual measurements.

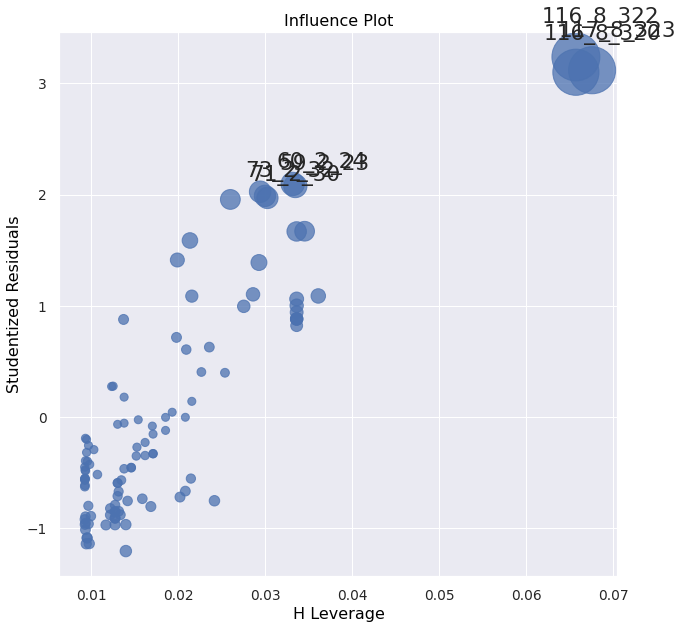

Analyzing data and looking at outliers (2019-11-24)¶

import statsmodels.api as sm

def plot_influence(df):

# TODO FIXME use it in prev section

res = sm.formula.ols("watts ~ rpm * resistance - resistance - rpm", data=df).fit()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 10))

sm.graphics.influence_plot(res, ax=ax, criterion="cooks")

plt.show()

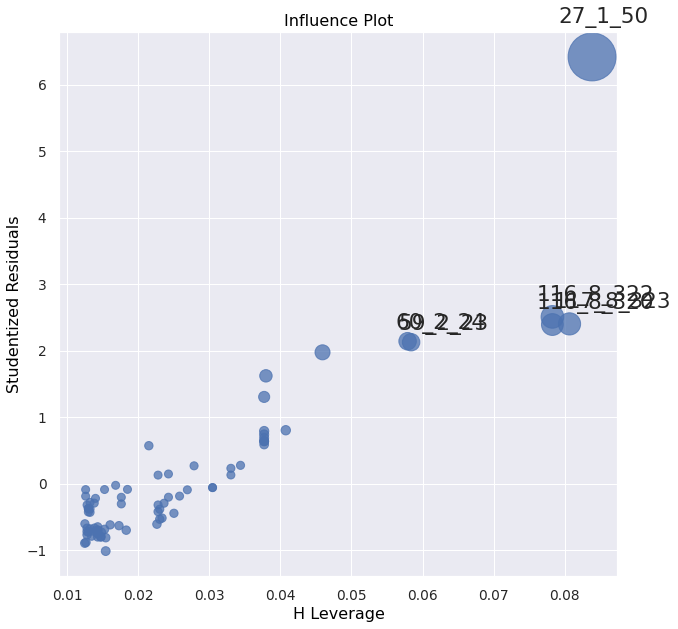

plot_influence(df)

# sm.graphics.plot_partregress_grid(res, fig=fig)

TODO hmm, 0.10 is not that high leverage right? Although depends on residual too, and here the residual is very high, so it would have high influence.. https://www.statsmodels.org/dev/examples/notebooks/generated/regression_plots.html

'27_1_50' seems like a typo. Let's drop it and ignore.

fdf = df.drop([

'27_1_50',

])

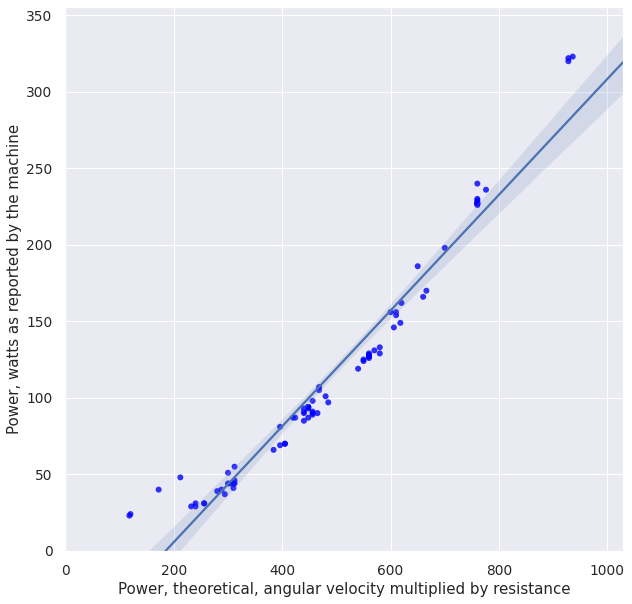

Ok, that's somewhat better at least in terms of outliers. Let's see if that helps:

plot_df(fdf)

print_stats(fdf)

So, on one hand that did make fit look more linear. On the other hand we've had to filter out all the low-resistance observations to achieve that.

I guess I'll collect more observations to be absolutely sure.

TODO add TOC or something?

Even more data (2019-11-25)¶

I've collected a bit more data, especially at lower velocities and resistance:

More measurements

new_df_2 = make_df("""

113 2 50

73 2 32

71 2 30

70 2 29

107 3 64

108 3 65

114 4 103

48 4 25

40 4 20

31 13 81

36 16 163

40 5 24

35 6 23

31 7 23

31 9 40

40 9 64

115 6 175

109 6 163

31 12 72

30 13 76

54 4 33

38 4 19

75 4 55

36 8 40

39 8 46

32 8 34

70 3 39

49 3 22

37 3 14

""")

ndf = pd.concat([fdf, new_df_2])

Let's check for outliers first:

plot_influence(ndf)

Residuals of 3 are borderline, but don't immediately mean outliers.

Let's plot and analyze! Just out of curiosity, in addition we'll color values corresponding to different resistances (the darker, the more resistance):

ress = list(sorted(set(ndf['resistance'])))

colors = dict(zip(ress, sns.light_palette('navy', n_colors=len(ress))))

ndf['color'] = [colors[x] for x in ndf['resistance']]

# if you know of an easier way to use column value as a color in seaborn, please let me know!

plot_df(ndf)

print_stats(ndf)

So, there is a clear trend of points clumping towards 0, which means that the model ceases to be linear.

If we try to fit the line to the points in a more reasonable exercise range (e.g. at least 50 RPM and resistance of 6, which would mean Power >= 300), that would skew the regression line even more to the right and move the coefficient even further away from zero.

So overall it means that either:

- the assumption of linear dependency on resistance and velocity is wrong, but then it's completely unclear how the power is estimated

- I wasn't accurate during measurements on lower intensities, but I think it's pretty unlikely as I did multiple measurement sessions and even if you ignore the higher variance, mean is still way above the regression line

- the velocity/resistance reported by the machine are wrong or misleading. It's possible that the number machine assigns to 'resistance' doesn't really mean anything.

Conclusion¶

¯\(ツ)/¯

I guess be careful about trusting the equipment and do your own experiments.

As you can see, my initial project of finding some correlation with my HR turned out in a completely different direction.

Next steps¶

Would be interesting to at least compare watts (theoretical and reported by the machine) versus calories estimated by Endomondo (which takes heart rate into account).